Safe Practice - Error Wisdom

Error Wisdom

Organizational accidents have their origins in system weaknesses, however, that does not mean healthcare providers such as doctors and nurses who are at the sharp end do not have a role to play in avoiding their occurrence.

Individual mindfulness is an approach that helps care providers to be error-wise by recognizing the situations that can lead to safety incidents.

Healthcare providers should be encouraged to acquire an attitude of individual mindfulness through education and training (Foresight Training) which will only be sustained in the presence of collective mindfulness and support from supervisors and organization leadership.

Heightened risk awareness is something that many healthcare professionals acquire as a result of long experience in the field. James Reason has proposed a model that can shortcut the experiential learning process by providing front-liners and often junior healthcare providers with training in identifying high-risk situations.

The Three-Bucket Model

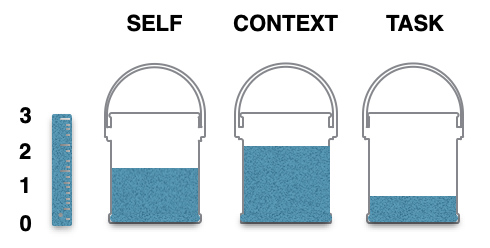

The three-bucket model is designed to impart error wisdom and risk awareness to individuals. The buckets correspond to the three features of a situation that influence the likelihood of an error being made (see Figure). One bucket reflects the well-being or otherwise of the front-line individual (SELF); the second relates to the error-provoking features of the situation (CONTEXT); and the third concerns the nature of the task and its various steps (TASK).

The SELF bucket relates to personal factors: level of knowledge, level of skill, level of experience, current well-being or otherwise. For example:

-

- a healthcare professional working at night is more likely to be affected by the consequences of shift work, such as fatigue;

- someone who has had a bad night’s sleep due to a sick child;

- someone whose partner has just lost their job.

The CONTEXT bucket reflects on the nature of the work environment: distractions and interruptions, shift handovers, lack of time, faulty equipment and lack of necessary materials. For example:

-

- a cluttered environment makes it difficult to see what equipment is available and whether it is being maintained or properly calibrated;

- a senior nurse arrives on duty having missed the handover and two members of his team are away sick;

- a new nurse does not know the layout of the ward.

The TASK bucket depends on the error potential of the task. For example:

-

- steps near the end of an activity are more likely to be omitted;

- certain tasks (e.g. programming infusion pumps) are complex and error-prone.

In any given situation, the probability of unsafe acts being committed is a function of the amount of ‘bad stuff’ in all three buckets.

However, the three buckets are constantly emptying and filling at any point in time in response to whatever is happening at that time. An empty bucket in the morning does not necessarily mean an empty bucket in the afternoon.

The key is having an awareness of the state of the buckets and developing strategies to empty them when they look full.

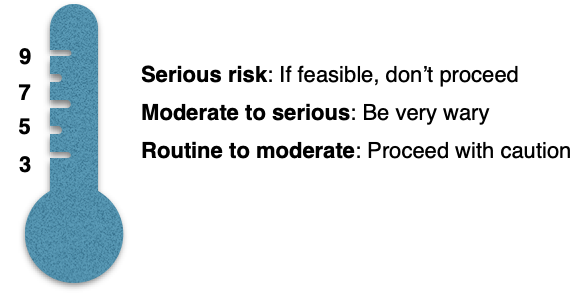

Full buckets do not guarantee the occurrence of an error, nor do nearly empty ones ensure safety (they are never completely empty) – we are dealing with probabilities rather than certainties. The contents of each bucket are scaled from one to three, summing to nine in total.

People are very good at making rapid intuitive ordinal ratings of situational aspects. Together with some relatively inexpensive instruction on error provoking conditions, front-line professionals could acquire the mental skills necessary for making a rough and ready assessment of the error risk in any given situation.

Subjective ratings totaling between six and nine (each bucket has a three-point scale, rising to a total of nine for the situation as a whole) should set the alarm bells ringing (see Figure). Where possible, this should lead them to step back and seek help.

The three-bucket model seeks to emphasize the following aspects of mental preparedness:

-

- Accept that errors can and will happen.

- Assess the local ‘bad stuff’ before embarking on a task.

- Be prepared to seek more qualified assistance.

- Don’t let professional courtesy get in the way of establishing your immediate colleagues’ knowledge and experience with regard to the patient, particularly when they are strangers.

- Understand that the path to adverse events is paved with false assumptions.

Example

A registered nurse arrived late to her evening shift to discover that she was all alone as her senior colleague was absent and not replaced. She had been hastily handed over the ward. One patient was to receive an IV medication which was not the right one and unfortunately led to his death.

Using the Three Bucket Model, the nurse could have realized that she was on an error path if she realized the following:

SELF bucket: Arriving late and being stressed.

CONTEXT bucket: Working alone in the shift.

TASK bucket: Omitting medication check before administration.

Reading Material

-

- Reason J. Beyond the Organizational accident: the need for “error wisdom” on the frontline. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(Suppl II):ii28-iI33.

- NPSA. Foresight training: Resource pack. London. 2008.

- Reason J. Organizational accidents revisited. CRC Press. 2016.